“They don’t have to show us Catch-22,” the old woman answered. “The law says they don’t have to.”

“What law says they don’t have to?”

“Catch-22.”

Catch-22, Joseph Heller

Konrad Mizzi, the government and anybody with an interest in transforming the Mizzi/Schembri Panama Papers issue into yet another story of apparent ‘allegations’ are crying victory all over the social media following the Appeals Court decision to overturn a lower court’s decision to allow an in genere inquiry (inquest-inkjesta) to go ahead into allegations of money laundering by the government’s star-minister.

Ignorance of the law has always been abused of and politicians will continue to do so, as long as citizens are happy to be taken for a ride. The Court decision today is all about not allowing an inquiry to go ahead. It does not exculpate Mizzi – far from it. The whole judgment reads as a technical examination on whether or not the grounds exist for an in genere inquiry to go ahead. In layman’s terms the Judge was examining whether the report that was made was substantial enough to justify starting an examination of facts in order to preserve such facts for what could eventually be a prosecution.

The worry in today’s Malta is that the systemic breakdown that includes the breakdown of the rule of law has affected every branch of our democracy’s institutions. Our Justice Minister constantly takes pride in reminding everyone who complains that, among others, we have a faultless judicial appointments system. And yet.

Yet the Venice commission report clearly pointed out faults in this appointments system. The judiciary remain firmly within the hold and control of the executive – particularly with regards to their hopes for their future career development. It would not take much to begin to wonder whether judgments are being written in reverse – a decision is taken and then an excuse for a justification for a decision that grasps at straws to sound “law-worthy’ is conjured up as a supposedly good reason to reach that decision that has already been decided.

Judge Grixti’s ruling is faulty. There is no harm in saying that because, as I know very well myself, drafters of judgments are far from being infallible. It is not enough to claim that it is faulty though – an explanation must be given. @bugdavem on twitter gave the perfect explanation in a thread that I am reproducing below.

I will only add that Grixti seems to have come up with a Catch-22 situation for anyone wanting to report a crime with the hope to get an inquiry in genere going.

It goes something like this: You need an in genere inquiry to investigate, find and confirm the existence of proof that may be used for a future prosecution of a crime. In order to get an in genere inquiry going you need to provide the type of proof that would normally be found and obtained by the in genere inquiry itself. See? Grixti’s very own Catch-22.

Bugdavem on twitter

The catch with Judge Giovanni Grixti’s ruling is (and this is where you realise that the Maltese courts have – intentionally or otherwise – no understanding of money laundering), that attempted money laundering is in itself a crime punishable by 3+ years imprisonment.

What does that mean or entail? Money laundering laws set a low threshold for evidence given that, in practice, the machinations that might be employed by launderers or attempted launders could frustrate justice.

In a case of actual money laundering, the threshold needed for the prosecution is prima facie – at face value – that there is no logical or lawful explanation for the monies to be laundered. The Maltese courts have held jusrt this in the past and it is also clearly stated in the law.

Once that is proven then it is up to the defendent to prove to the satisfaction of the court that any monies and arrangements were in fact lawful and legitimate. This is the rule for actual money laundering as well as the threshold and burdens of proof required.

For attempted money laundering, the threshold is even lower since given that this is an “attempt” one would need to show prima facie the intention and preliminary steps taken to implement that intention.

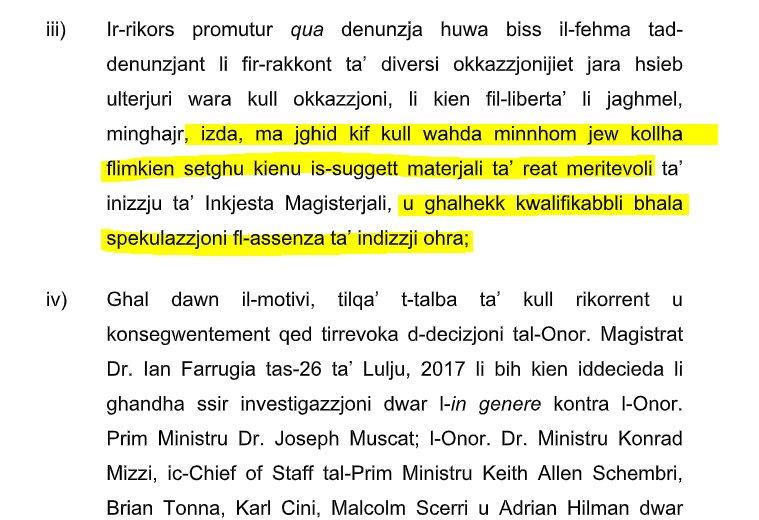

In Judge Giovanni Grixti’s decision to reject even the opening of an inquest to saveguard evidence (ie, not even for a prosecution so the threshold is actuallylower) he ruled that he expected a level of evidence that is higher than the prosecution in an actual case of laundering .

This is the active part where he stated that is was incumbent on the complainant, here Simon Busuttil, to prove how the series of events and machinations were illegal (as opposed to the threshold of prima facie no logical or lawful explanation).

Anyone with half a brain can see how bizarre this is. The threshold to request a magistrate to safeguard evidence in attempted laundering which the Police won’t investigate is (by virtue of this judgment – J’accuse) actually (set) higher than that required by the Police to secure a conviction for actual money laundering.

One reply on “Judge Grixti’s Catch-22”

[…] Read his full article here. […]