J'accuse: Stable government and its price

So David Cameron got to move to number 10 after all. With a little help from his new-found friends, Cameron (and Clegg) ushered in an era of “collaborative politics” that promises to combine effective representation with reasoned administration for the greater good of the people. The much-maligned monster that is coalition government settled in and is already working on an Emergency Budget to tackle the continuing ails of the economy (British, European and worldwide). And there we were thinking that pesky third parties would ruin the show.

When the pros and cons of coalition governments are being discussed, the question of stable government always figures as one of primary concern. The fear of government breaking down or collapsing mid-term and of provoking multiple elections over short spans of time have been one of the main arguments against the possibility of coalition governments – that and the ugly duckling of a “kingmaker” party – a minor party able to call the shots on who gets to form a government.

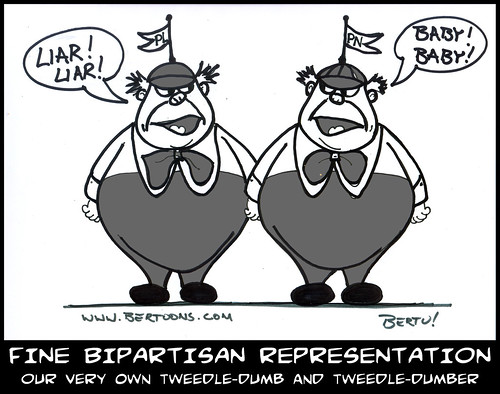

Whenever such considerations are made we are making implied choices between stronger representation and stable government. The implication seems to be that perfect, proportional representation is not conducive to stable government. In a way that is because, given our “black or white” bipartisan all-or-nothing approach, we are automatically suspicious of compromise politics and confidence building. But is our “stable government” system really so perfect after all?

Stable or bust

Speaking to the party faithful at the PN General Council on Friday, minister Tonio Borg reassured those present that “the government will be safeguarding the people’s clear verdict given in the general election two years ago which was for the Nationalist Party to govern the country for five years.” This was Tonio’s summary refusal of the PL thesis of a government hanging onto power by its talons. Forget Auditor General investigations, forget disquisitions on Erskine-May and forget companies with ugly acronyms like BWSC.

It’s all about who is in power for five years. The reverse side of the coin is the same. Look at the fracas in parliament – the yelling, the motions, counter-motions, the childish insults and defences (you’re drunk and she’s pregnant – oh the shame) – it all boils down to one thing and one thing only: the PL wanted so desperately to bring this one seat-majority government crumbling down (on a vote which technically does not do that) and to undermine whatever sense of legitimacy GonziPN still has to govern.

When the results of the last election were out, our Bertoon had Gonzi celebrating on a small bucket representing his “relative majority”. A party that garnered less than 50 per cent of the vote in the country would govern, thanks to a constitutional mechanism of seat compensation. Our caption read: “D’hondt worry, we’re happy” – a nod to the D’hondt system of calculation in elections – invented by a Belgian (Belgian? now that’s a sure source for stable governments). The toon was our way of saying “at least someone’s happy”. Sure. GonziPN had every right to be happy as the next legitimate government of the nation, having snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. But was the voter really getting a good deal in constitutional and representative terms?

The cost of ‘stable government’

Two years ago a party that had a 1,500 vote advantage over the next party that had failed to get to the 50 per cent threshold could claim two extra seats in “constitutional compensation”. Those two extra seats (voting value approximately 7,000) are given to the party with the relative majority in order to ensure that it can govern for the next five or so years – assuming that all the members on its side of the House will vote in its favour.

So we have constructed our “stable government” around a fictive majority that in effect exercises something akin to absolute legislative power in parliament. If government wills it, anything becomes law – unless its bench members decide (knowingly or out of fatigue) to vote against it. The Opposition may – rightly or wrongly – yell, cry, perform its least flattering resurrection of 80’s parliamentary thuggery, walk out in indignation and shout “foul” to an angry nation. It may do all that and more but, barring a revolution, the government is as firmly in place as a limpet – crisis averted, n’est-ce pas?

There is no coalition partner forced upon a party that has not obtained the majority of national votes. No coalition partner to act as a moderator of the more radical of the government policies that might only have enjoyed the favour of a national minority (relative majority it well may be, but it is still a government by national minority). The closest we can get to the coalition partner scenario is in the infamous “rebel backbenchers” picture where, for reasons that can be highly volatile (not as clear as those of an elected coalition partner), a fraction of the party in government decides to make use of his newfound disproportionate weight.

I don’t know about you but if that’s stability, then give me instability any day. Not that I would want instability, but this kind of conundrum really makes the examination of an alternative scenario with coalition partner worth revisiting. AD chairman Mike Briguglio wrote of the current state of affairs in an article that also appeared in J’accuse (Symbol of a Stagnated Duopoly). At one point Mike suggests that the Nationalist Party might even pull off a victory at the next general election. What then?

Mike wrote: “The Nationalists can save their day if the economy recovers, yet, if in government alone, in the next election, we can only expect more arrogance, disregard for the environment, confessional politics and a lack of civil liberties and social rights.” The “if in government alone” bit did not escape me. It is obvious that AD of all parties would entertain thoughts of coalitions in Clegg style and Briguglio’s message is clear – if the Nationalists were to be part of the next government it would best be with a check and balance system guaranteed by a coalition partner.

The problem in Malta is that voters will weigh this option with the usual suspicion. Elections are depicted as an all or nothing battle themselves. The rules are such that – as I have shown – the trophy of governance is intricately merged with the trophy of absolute power at all costs. Even in such telling times as these, when the bipartisan representation exposes all its ugly warts, messengers like Briguglio will find it incredibly hard to sell the idea of a different form of “collaborative government” that has just been launched in the UK. Selling the idea might not be enough – without electoral reform, laws on party financing and a clear awareness among the voting population, we are far, very far, from being anywhere near the kind of movement that brought the UK Cleggmania.

Meanwhile the BWSC saga with all the parliamentary repercussions rolls on. Joseph Muscat of the Same, Same but Different Party has just presented his 15 points to battle corruption. The monster, once defined, failed to bring the PN government down. So now Don Quixote invents a few swords and sabres and bandies them about. We shall see how gullible the voters can be by the way they accept this new set of “promises”. In our analysis of the 15 points on the blog we point out (among other things) that:

(a) promising a working electricity system is just the mediocre kind of electoral gimmick you can expect from our bipartisan stable system in the 21st century; (b) you cannot fight corruption if you are unable to define it legally; (c) there is no such thing as retroactive application of criminal law; (d) when Joseph Muscat promises to implement a directive he is stating the obvious – he will have to implement directives when in government whether he likes it or not; and (e) a law on party financing must not be limited to “corruption” whatever that means – transparency means knowing even what are the “legitimate” sources of party funds.

Somebody stabilise that euro

I know it’s egoistic of me but I have begun to notice that ever since I booked a June trip to New York, there seems to be a general conspiracy to threaten my holiday. As if Iceland’s bucolic volcano and its random outbursts of paralytic ash were not enough, the combined effect of Greek woes and economic disaster on the continent have daily gnawed away at the purchasing power of the beloved euro, once I cross the pond to the other side. Also, if you please, those bigoted maniacs that fabricate religious excuses at the same rate as they strap bombs to their chests have upped the ante once again in the city that never sleeps.

Conspiracy or no conspiracy, I have “New York or Burst” (as Balki Bartokamous would have it) tattooed on my brain. No volcano, euro devaluation or fanatic terrorist will come between me and the joys of the 24-hour Apple Store on Fifth Avenue – open 24/365… beat that GRTU! How’s that for stable determination?

www.akkuza.com has been on a go-slow this Ascension Long Weekend in Luxembourg. We’ll be discussing stable governments all next week so do not miss out on the action.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Will a coalition government be bad for Britain? (cnn.com)

- Debunking the latest arguments in favour of first-past-the-post (leftfootforward.org)

- Coalition government – live blog (guardian.co.uk)

- We want a 55% threshold because Britain needs stable government | Oliver Letwin and Danny Alexander (guardian.co.uk)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=37d347b4-9541-4c91-88e2-94c9724dc9b8)

Cleggmania and the coalition gov in the UK have a history, unlike Malta, where people have always had the idea of a bipolar way to politics. That’s a tough mould to break.

Sorry, but if there’s anything “fictive” that’s your mathematics.

Strict proportionality for a 65-member parliament would have given the Nationalists 33 seats to Labour’s 32. “Classical STV” actually gave Labour a majority of three seats. That’s two seats proportionality would not have entitled them to or, by your reckoning, attributing to them 7,000 votes they didn’t get.

That extra seats went to the Nationalists rather than excess seats were deducted from Labour’s count is only because the compensatory mechanism works that way: adding seats rather than reducing them.

Rather than fume at the Nationalists who, at no juncture of the process, benefitted more than they were entitled to, you really ought to be questioning the system — from STV to districting — that would have given Labour a three-seat majority were it not for that “consitutional compensation” you malign so much.

Round and round we go. Yes. The result, had we to calculate strict proportionality on votes cast under the current system would have given PN 33 PL 32. unfortunately we cannot know if the votes cast would have been the same had voters known that perfect proportionality would apply. Which is the eternal chicken and the egg.

On the other hand the argument being made here is whether it is preferable to have a coalition or a false majority of seats (yes false, proportional or not none of the parties got more than 50% of the votes) – is it preferable to be at the mercy of renegade backbenchers or to be able to clearly know the conditions of what will make or break the majority?

We will never know will we?

Bah, why did I assume that it was obvious that the point was about the Greens or any third party outfit?

I should have remembered that you fume over the fact that the compensatory mechanism gave extra seats to the Nationalists giving little regard to the fact that, if it didn’t do so we’d have had a situation where a party that does not even have a relative majority of votes ends up with an absolute majority of seats.

Er, lapsus. Meant to say that the point was NOT about the Green Party.

*snigger* he said lapsus *snigger*