Is Bill 125 challengeable under EU Law?

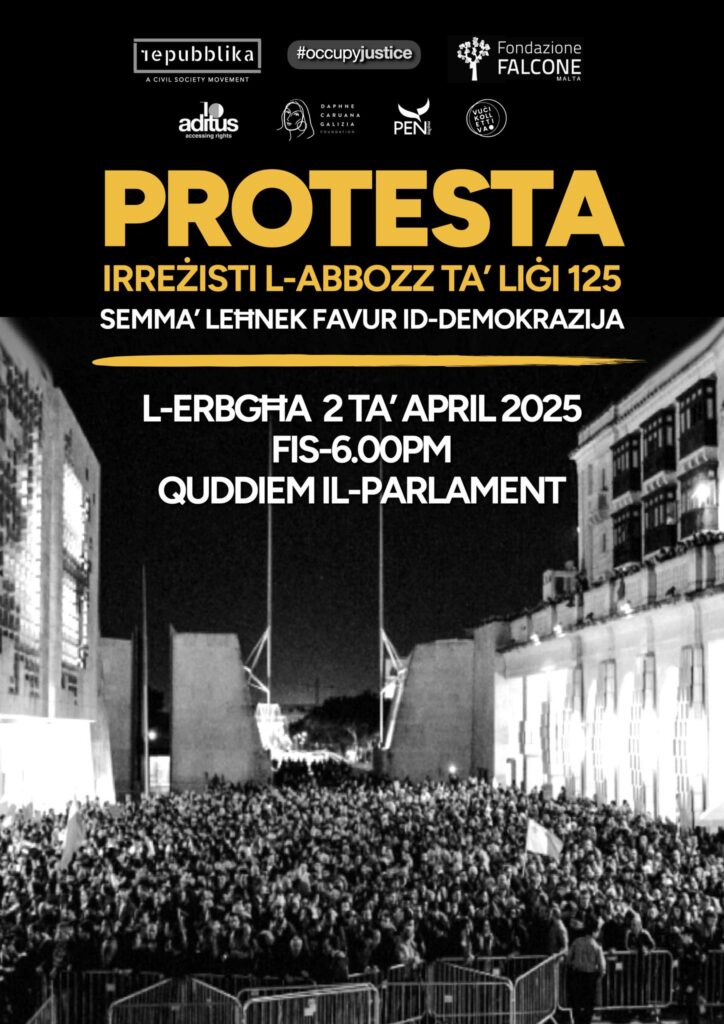

Wednesday’s protest outside parliament is all about challenging Bill 125. Repubblika has already registered a court protest against the bill, showing a clear intention to use all legal avenues to stop it from coming into effect. One of the main criticisms of the Bill is that it signifies a step back, and not forward, in the protection and safeguard of citizen rights by weakening what has proven to be an effective tool in the control and supervision of executive power.

It has been argued in some circles that one possible avenue of challenging the Bill (or the law once it comes into effect) is by arguing its incompatibility with Malta’s EU obligations. In other words, the law would constitute a breach of EU law. More specifically, the nature of the law would be such that it would constitute a violation of the Principle of Non-Regression. Government exponents have been quick to shoot down this potential avenue of redress, claiming that the aforementioned principle is only applicable to judicial reforms. Bill 125, limited to reforming in genere inquiries, would not fall under that principle – at least that is what they claim.

Since its explicit acknowledgment in the Repubblika judgment (Case C-896/19), the Principle of Non-Regression has emerged as a significant instrument employed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to safeguard the rule of law within the EU. In Repubblika, the Court articulated a clear prohibition on national reforms that diminish judicial independence, reinforcing the idea that once an EU Member State attains certain standards of protection for judicial independence, regressive measures are not allowed.

Following Repubblika, the CJEU has consistently reiterated that maintaining attained levels of judicial independence and rule of law standards is not optional but obligatory for Member States. For instance, this principle was underscored in subsequent rulings, where judicial reforms proposed in various Member States were scrutinized for potentially weakening pre-existing standards.

However, an essential question remains: does this Principle of Non-Regression apply solely to judicial independence, or can it extend to other fields of EU law?

The broader interpretation, emerging from doctrinal debates and scholarly analysis, suggests potential applicability beyond the judicial sphere. Although initially associated explicitly with rule of law contexts, non-regression could logically extend to other fundamental areas safeguarded by EU law, including environmental standards, social rights, and consumer protection. In fact, the broader application aligns with EU objectives to ensure continual progress toward enhanced standards, reflecting an underlying EU constitutional ethos aimed at safeguarding and progressively developing established protections.

Nonetheless, while the theoretical scope for such broader application exists, concrete affirmation by the CJEU outside judicial contexts is yet to materialize definitively. While Repubblika has solidly anchored non-regression within judicial reforms, its extension into broader domains remains a dynamic, evolving area of EU jurisprudence, awaiting further clarification from future case law.

In any case it is not at all a given fact that a potential challenge of the Bill 125 made law based on incompatibility with EU law would be thrown out by the EU court. The principle of non-regression, enshrined in another Malta-related case is clearly ripe for the use against laws such as Bill 125.

This would be even more the case should it be proven that by enacting Bill 125 Malta is failing its obligation under article 19 of the TFUE: “Member States shall provide remedies sufficient to ensure effective legal protection in the fields covered by Union law.” It could be argued that this article 19 obligation encapsulates the citizen’s right to access inquiries that is being curtailed by Bill 125. “The fields covered by Union law” would incidentally include issues such as corruption related to EU funds that may be the subject of such inquiries.

In short, the odds are strongly in favour of any such challenge. I harbour little doubts on the admissibility of such an action and less on its success.

Besides the (ill-) legality of it all, the basic principle of giving the people the power to check and balance all activities of government and its affiliates, remains sacrosanct.